|

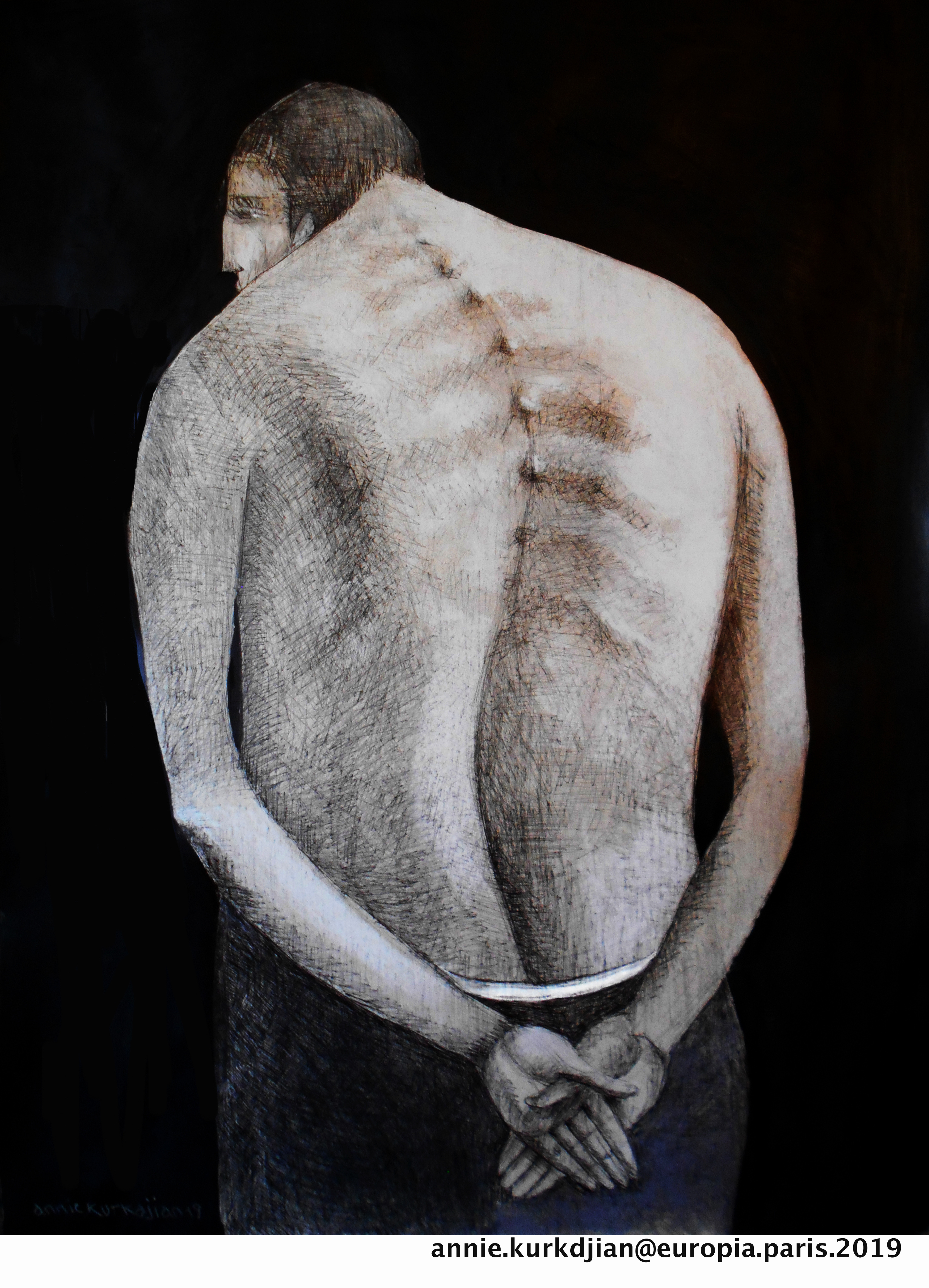

" ... The horrors of war and the trauma of loss find their way into her work with warm intimate metaphors: Transformations of the body, psychological horror, paralysis and deformity. Kurkdjian's painting presents a vast range of apparently figurative possibilities that demand not just contemplation but a great degree of attention and empathy. Some of her paintings can be conceived as academic studies on fear and psychosis: How do I represent myself through different stages of torture, mutilation, psychosis, and ultimately redemption. The soul is painted bodily through the mirrors of modern life: War, annihilation, despair.

Her complex iconography is a visual narrative, construed not only as the expressions of somber material realities and how they would be represented if we could speak about them, but also as a cultural journey through contemporary philosophy, poetry and film. Re-writing life not only without limits, but precisely at the very limit where the human condition becomes tragedy and comedy, caricature and cinema, allegory and hallucination. Unlike most artworks examining the conditions of trauma and womanhood, Kurkdjian focuses not only on the victims of war and violence, but also on the victimizers and their environments.

While there is a Surrealist element in her work, with its tendency to reconfigure reality at the mercy of violence, the painter keeps looking for the place of love and dignity in life through humorous, often laconic references. The constant search for skeptical spirituality brings her closer to the Belgian painter René Magritte, who was not interested in painting the world as a dream but rather, in how we would experience it if we were truly awake, and not half in slumber through the endless anesthetics of modern life. Annie Kurkdjian, as an artist, wants to live with the illusion of living without illusions and yet at the threshold of hope.

Unlike Magritte, however, Kurkdjian's faces are not abstract but distinctively human and always at risk: Scenarios of pain, expressions of fear, abandonment, sarcasm. Sometimes childish and sometimes voluptuous; suspended in smooth animated backgrounds, her characters are captured with the unsentimental empathy of Diane Arbus' photography: Alien, hopelessly isolated, immobilized in mechanical, crippled identities and relationships (Susan Sontag). The grotesque and the shameful, the private and the intimate, become in her paintings, metaphors for being subject to violence, to mistreatment, to mercilessness.

But there is more thirst and anguish than hopelessness and anger in her work. The endless transformations that the human person undergoes in her canvas is also a mapping of the journey of art between the restrictions of traditional painting and the constant fluidity of life in her native Middle East, between peace and war, hate and love, indifference and warmth. The precision of Kurkdjian's eye is such that she doesn't look the other way when confronted with horror; instead she attempts to transform pain into a theater of life. Or, in the words of Helene Cixous: "Everything that is (looked at justly) is good. Is exciting. Is "terrible." Life is terrible. Terribly beautiful, terribly cruel. Everything is marvelously terrible, to whoever looks at things as they are."

Text presented by" Albareh Art Gallery" @ Art Dubai 2013 |